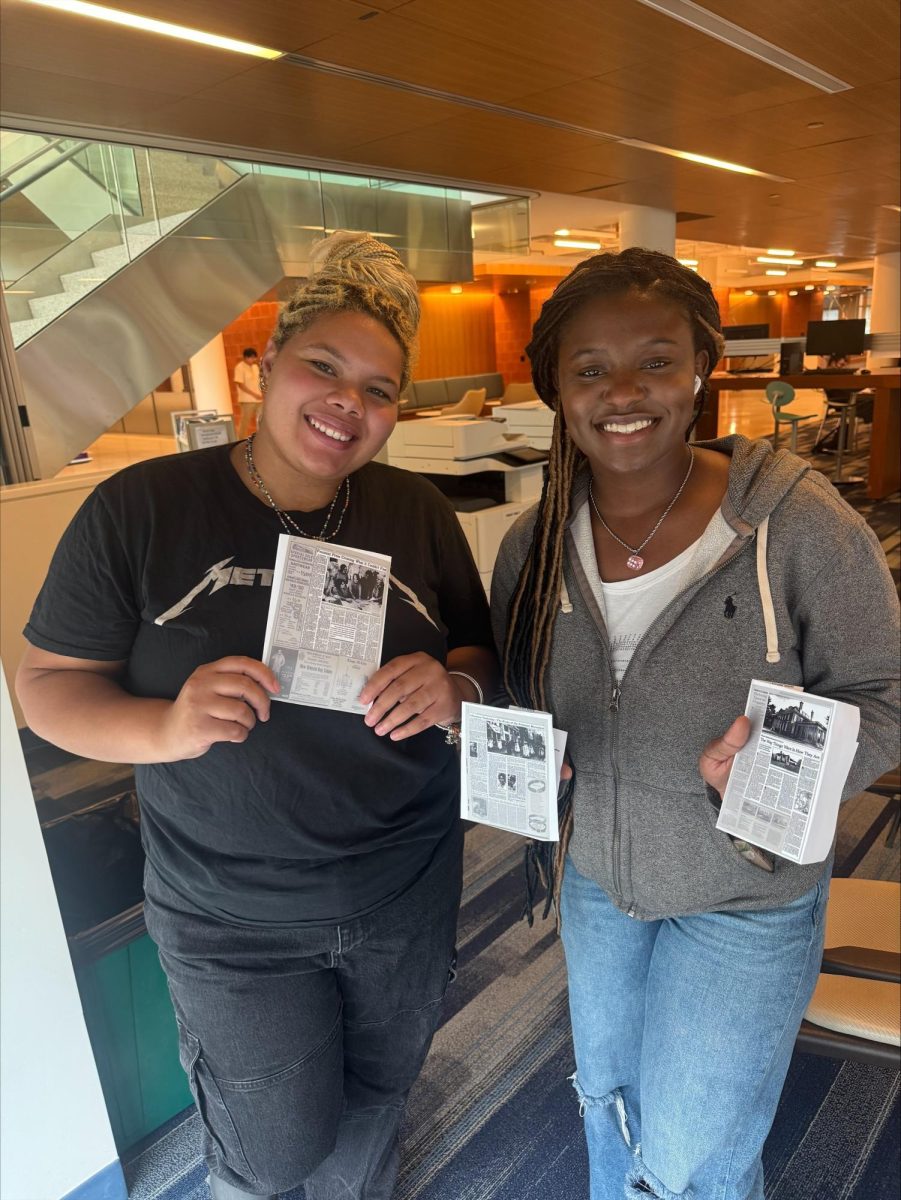

SUNY Old Westbury students hold reproductions of early Feminist Press publications on Sept. 26, 2025, connecting the campus’s activist past to its present-day academic community. PHOTO BY: DESPINA DRAKOPOULOS

The Feminist Press, a book publishing house founded in 1970 by scholar Florence Howe, began as a small publishing project at SUNY Old Westbury and has since grown into an internationally recognized publisher with more than 500 titles distributed across 80 countries, according to a 2020 Forbes article.

Its mission, rooted in social justice and women’s scholarship, continues to influence academia and activism more than five decades later.

Howe first launched the press from her Maryland apartment. When she was recruited to SUNY Old Westbury as a professor of English in 1971, she was encouraged to bring the project with her.

“She had started the Feminist Press to create an outlet for women’s scholarship at a time when it couldn’t find publishers,” said Professor Jillian Crocker, a faculty member in SUNY Old Westbury’s Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program, commonly referred to as WGSS.

A time when women’s voices were largely absent from classrooms and publishing houses, the press offered a crucial platform that reshaped both literature and academia.

“At first they were reprinting overlooked works, but they also became a platform for new feminist scholars,” Crocker said. “That was crucial for the development of women’s studies as an academic discipline.”

Professor Frisken, also part of the WGSS at SUNY Old Westbury, said the broader campus climate helped give rise to the publication.

“1968 was an exciting and terrible year on college campuses,” she said. “There was so much optimism and enthusiasm for change, and yet there was war and division. That environment inspired activism like the Feminist Press.”

The college provided Howe with office space and faculty backing at a time when funding was scarce, Frisken said.

“It’s really hard to make a lot of money, especially at that time,” she said. “Having space on campus and support from colleagues kept it alive.”

Recent nonprofit filings show the Feminist Press generated more than $1.6 million in revenue in 2023, with the majority coming directly from its publishing programs and the rest supported by contributions and grants.

It has come a long way since its beginning, Crocker said, thanks in part to the university’s support that was crucial during the publication’s formative years. And the Feminist Press has had a lasting impact on the school as well.

“The reality is WGSS, as an academic discipline, heavily relied on the work of the Feminist Press,” Crocker said. “We wouldn’t have feminist intellectual work reaching the impact it did without the press creating a forum for it.”

She added that faculty at the time often faced resistance in their fields, but the press gave their scholarship legitimacy. The press also played a symbolic role in shaping SUNY Old Westbury’s academic identity.

“We have photos on the wall of the historians and feminist scholars who built this field,” Crocker said. “We are literally standing on their shoulders.”

Both professors also noted the press’s enduring relevance.

“The scholarship supported by the Feminist Press gave women a voice in academia when they were largely ignored, and that impact is still felt today,” Crocker said.

Frisken noted that today’s student activism reflects the spirit of the 1970s.

“Whether it’s climate justice, racial equity, or gender rights, students now—just like then—are motivated by knowledge and a sense of belonging to larger movements,” she said.

Sixty years after its founding, the Feminist Press remains a global force that continues to challenge assumptions and expand conversations. For SUNY Old Westbury, its legacy is a reminder that scholarship and activism can transform the world when institutions invest in bold ideas.

What began as one woman’s vision in a small Maryland apartment endures today as proof that knowledge, once given a platform, can change history.

“We recognize the diversity of voices today because of the work of the Feminist Press,” Crocker said. “I can’t even imagine a world without it.”