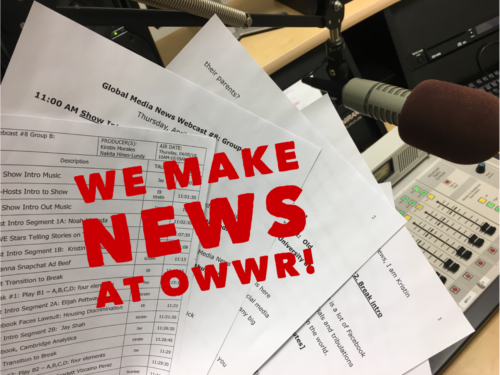

This Week on Global Media News:

- WWE Stars Beef Up Their Social Skills on Twitter.

- What Did Snapchat Do to Make Rihanna Angry?

- Facebook Sued Again? What’s Housing Discrimination Got to Do With It?

- What Did Cambridge Analytica Do With All That Facebook Data?

- Will Vero Be the Next Social Giant? Why?

- College Students Drink: Chinese University Sends Photos to Parents?

Global Media News is a weekly webcast covering new media news from around the world. GMN is a production of Media Studies students from the SUNY College @ Old Westbury. We scour the web for news about new media, journalism and technology.

Listen to our next podcast streaming live on OWWR: Thursday April 12, 2018 @ 10 am EST.

Can’t listen live? Our next podcast will be posted by 2:00pm, Thursday April 12, 2018.