What are the politics of reading banned books in America? How does book-banning present a threat to inclusive learning and critical thinking? How is the impact felt by both curious learners and educators in our academic environment?

On Wednesday, March 13, Professors Jillian Crocker, Stephanie Schneider, and Amy Hsu led a thought provoking discussion of these questions in the Women’s Gender & Sexualities Studies center (WGSS).

As the discussion began, students shared why they read books. The responses varied from “escaping reality” and “hearing the stories of others” to “expand your creativity” and to “broaden my understanding of the world.”

Professor Schneider encouraged students to get ahold of books that have been banned. “If you really want to know about a society, look at what they’re not reading.” She added, “Look at what they’re afraid of.”

Dr. Schneider noted that the dictionary, as well as the Bible, have been banned in particular districts in Florida because of their “suggestive” nature. These are just a fraction of the “unauthorized” texts that both administration and parents are fighting to be taken out of school curriculums.

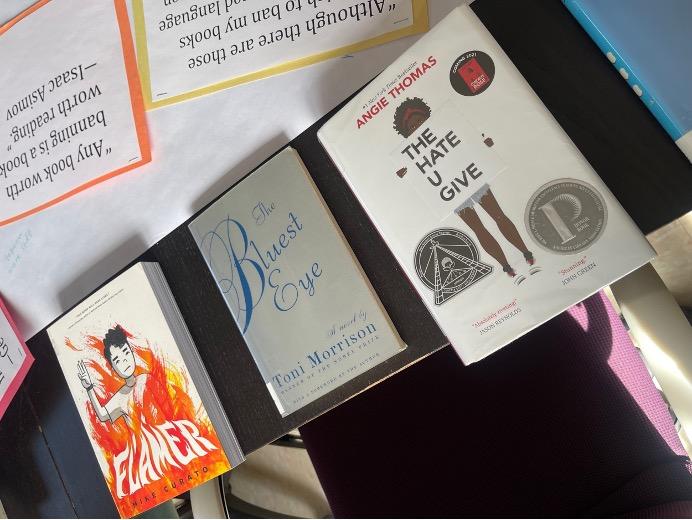

A collection of library books deemed unsuitable for classrooms was displayed on a table during the discussion, including “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison, “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas, and “The Hunger Games” by Suzanne Collins, to name a few. The themes presented in these books include government resistance, racism, police brutality, classism, inequality, identity, and activism. Many of these issues are being censored in the American education system.

Libraries and schools banned more books in 2023 than any other year in U.S. history, with over 4,000 targeted book titles, according to The Guardian. Many of these banned books were specifically targeted because of LGBTQIA+ or race related subject matter.

Why is there an attack on free speech? Why are there so many attempts to control the narrative of American history and society? Why should the stories of others go unheard because of personal discomfort?

Professor Schneider posed a question, “What are we trying to protect our children from?” After reading “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe, the most banned book in America, she began to question if Schneider would allow her own son to read it. She believes in making literature accessible to children who may need to read it, even if it might make her uncomfortable.

Professor Crocker noted that these challenges aren’t just limited to the titles alone, but to the authors themselves, who are often ostracized being women of color.

Professor Hsu encouraged some critical thinking about book banning.“What makes a book worth banning?” she asked. The group pondered the appropriateness and necessity of certain texts, imagery or symbols. She recognized the importance of active involvement in childhood education, and being familiar with the curriculum, instead of fighting against it.

The discussion at the WGSS center recognized the impact of literature and how important it is to share diverse perspectives within a classroom. These ideals are slowly fading as threats of censorship grow in the United States. Reading is an important part of learning for children and scholars. Book bans hinder learning, misrepresent historical narratives, and further skepticism of the educational system.

Professor Hsu shared a quote by Isaac Asimov: “Any book worth banning is a book worth reading.”