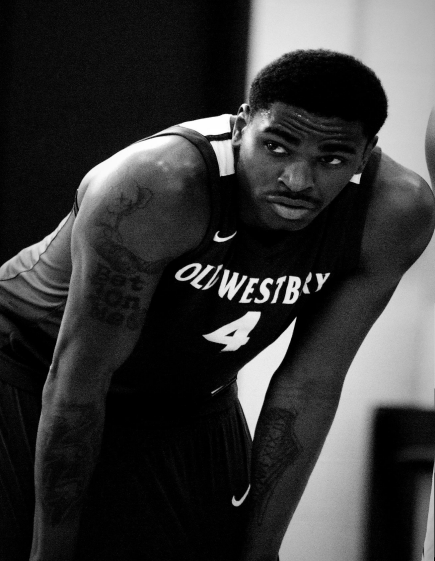

From September 16 to October 11, Old Westbury’s Amelie A. Wallace Gallery exhibited a small portion of Eric Edwards’ extensive collection of African art. The exhibit, titled African Art and Its Historic Value Systems in Educating a People, was an enlightening showcase of the craftsmanship of African artifacts. All information for this article was provided by literature handed out at the gallery, or during the collector’s talk on September 26.

Students looking over map of Africa

Dr. Eric Edwards has dedicated most of his life to collecting African art. At the talk, hosted by O.W. President Timothy Sams at the Duane L. Jones Recital Hall, Edwards expounded on his life, not only as a collector but as a human being.

Born and raised in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, Edwards’ father (an immigrant from Barbados) taught him about the history of Africa and its diaspora. “He was aghast to learn that no school in New York City taught about African descent,” he said. “What [my father] did was lay the groundwork to let us know we were somebody.” This proved to stay with him and he’s taken up a similar role in his old age.

Edwards had already been collecting audio recordings (which is another passion of his), but his fascination with artifacts started when he was a young man. “In 1971, I took an interest in African artifacts entirely by chance,” he said. When walking through SoHo, on break from his job at AT&T, Edwards found a small piece of African art that caught his eye. He turned to go back to work, but something made him look back; he needed that piece. It cost 300 bucks, and he placed it on his desk at work. Later, he researched the artifact he had purchased, sending him down his life’s path of collecting artifacts. “The pieces have stories to tell,” he said, as a way of justifying his passion.

Educating is the key principle here. As his father educated him about Africa and its people, so will he for future generations. Obviously, there is something to be said about hoarding artifacts instead of having them held by the state-inheritors of the culture. But, as Edwards himself said, “I don’t consider myself an owner, I’m a caretaker.” He is acting in good faith, using his collection as a tool to teach. As far as I know, he amassed this collection with the almighty dollar, not from some cruel imperial treachery; or maybe those two things are the same…but I digress.

Sams and Edwards talk

In November of 2023, Edwards opened the Cultural Museum of African Art, a center which hosts his entire collection. Located in his childhood neighborhood of Bed-Stuy, Edwards claims to have seen people so moved by the pieces that they cry. “The beauty grabs you, but when you look deeper you find a story,” he says.

Dr. Edwards standing next to a Songye Power Figure

For the portion of the collection that was on display, Edwards chose 16 sculptures from Sierra Leone, Angola, Gabon, Congo, Cameroon, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Guinea, and Mali. The artifacts from Cameroon are specifically from the Bamum people, which is noteworthy because of O.W. ‘s recent royal visit by the Bamum Sultan. The artifacts range from helmets, masks, figures and shrines. “They weren’t created for art’s sake,” Edwards said. “They had a much deeper purpose.”

Often we are told by stereotyped media that African art is primitive; the ‘cradle’ of civilization, a land of tribes and simple weapons. But some of these artifacts show a rigid, sophisticated naturalism. The Ife Cast Bronze Head of Oni King is a prime example of this. Dating from Nigeria (a Yoruba people) in the 1500s, the head is meticulously detailed to the point where it felt like looking through a glass wall into the past.

Ife Cast Bronze Head of Oni King on display

Much of the art on display were created by skilled artisans, and used for right-of-passage ceremonies. The Mende Bundu Sande Secret Society Helmet, is one such artifact. Originating from the Bundu Mende people of Sierra Leone, the helmet is topped with a crest, symbolizing the authority of the headmistress of these “secret societies,” who would teach them their gender-based lot in life. This is a form of learning that has prevailed throughout human civilization; an older, presumably wiser, member of the society teaches the youngsters how things go.

It’s as if Edwards had a divinely guided interest in these artifacts. Maybe those same spirits that make museum goers weep, called him to collect. Those accumulated ancestors, generation after generation, beckoned him to the art.

As mentioned earlier, Edwards said he doesn’t see these pieces as art, and it’s true they served a spiritual purpose, but the fact remains that the sculptors were artists in the same vein as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. Artists with a skill that drew royal and religious authorities alike to use their honed talent.

One of the Mende Bundu Sande helmets

The title of the exhibit is verbose, some might call it over indulgent, but the length is necessary. It tells people that this isn’t just some rich playboy’s collection, it’s an experience; one that the viewer will be all the better for. We’re following in the footsteps of learning. These artifacts were used to teach generations ago, and now here they are again – teaching in a whole new context.

To see more of the collection be sure to visit the Cultural Museum of African Art at 1360 Fulton street in Brooklyn, and book a tour online at https://cmaaeec.org.