The “Our Land” exhibition is comprised of photography and videography by artists from the Middle East, North Africa, and their diaspora as quoted in a statement by the exhibit and is curated by photographer and adjunct visual arts professor of Old Westbury Anthony Hamboussi. The first level of the exhibition features works from artists Rhea Karam (“Breathing Walls”), Manal Abu- Shaheen (“Beirut”) and Camille Zakharia (“Al Bar”).

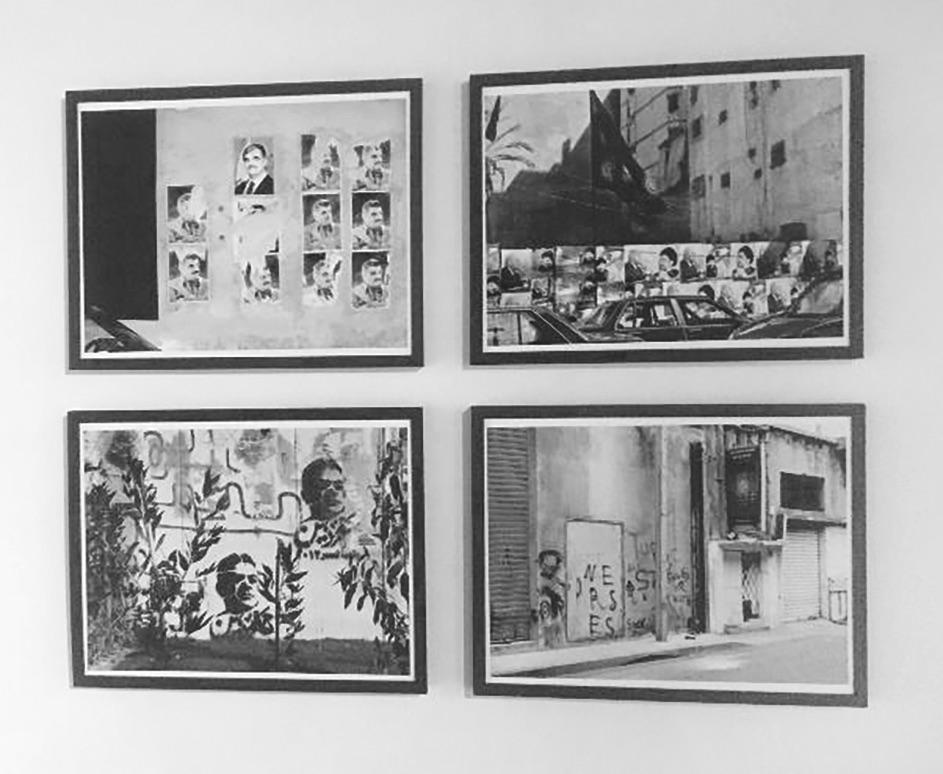

The upper-level exhibition captures its onlookers with a series of intricate colored and black and white photographs. The photographs feature pictures of people, places, neighborhoods, and art almost as if to indicate a culture. In Rhea Karam’s photographs “Breathing Walls,” there is a heavy presence of buildings and art decorated walls which is likely a testament to her focuses on urban landscapes which she began documenting in Lebanon in 2007 and 2009 (Our Land 4). What stood out most in her work in the feeling of familiarity it is as if you are in the places that are pictured, or you know them well. I believe the urban landscape helps those who may not understand the historical background to connect on a more intimate level.

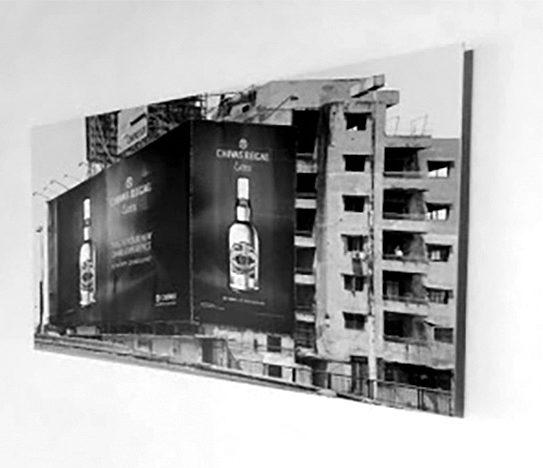

The black and white photographs from Manal Abu-Shaheen’s “Beirut” and the vibrantly colored photographs from Camille Zakharia’s “Al Bar” both contrast and complement each other as they sit on adjacent walls. In “Beirut,” we have billboards advertising excitement and beautiful faces. The choice to make them black and white gives the pieces a regal feel. Shaheen’s motivation for “the lack of visual history of the landscape of Lebanon” is what has drawn her to portray a city dominated by billboards (Our Land 2). In one sense, these advertisements serve as visual proof of capitalist growth, while in another sense they support a mythologized Western ideal that is incongruous with life in the post-conflict city (2).

Then as we move to the wall shouldering that one, we are awakened with brown, orange, red and tan colored tents in the desert. While the tents in the photographs are vacant, we see decorative rugs and furniture in and outside of them indicating their use. Zakharia uses these photographs to allure the viewer and portrays the transformation of Al Bar, a normally arid and lifeless area that comes alive between November and March (Our Land 5).

As we make our way to the mid-level gallery, we are invited into a space of not only photography but videography. The mid-level gallery features work from Youseff Chahine (Cairo), Rana ELNemr (The Khan), Anthony Hamboussi (The light that remains), Moath Alofi (The Last Tashahhud), Rania Lee Khalil (The Pan African-Asian Women’s Organization, Cairo and Conakry 1960-1965) and Aisha Mershani (Apartheid wall).

A small television screen in the right corner of the gallery features Chanine’s piece Cairo with a suited man talking in the middle of a busystreet. As we move around the gallery, we see the photographic works of Rana ELNemr and Anthony Hamboussi in The Khan and The Light that remains. In The Khan viewers are captivated by the angles and perspective in which the artist chose in his photos. The way the light hits the areas of the photograph in some and the shadows dominate in others makes the spaces seem hidden. In contrast, The Light that Remains uses the brightness of the day to highlight different objects and ruins. “ ‘The images highlight the waste and decadence of a shortsighted tourist industry and government policies that erased the indigenous Bedouin population (Our Land 3).”’

Next, we see a series of strategically captured buildings in Moath Alofi’s The Last Tashashhud which shows “’neglected mosques strewn along the winding roads that lead to the holy city of Al Madinah Al Munawerah (Our Land 2).”’ Following that is the video installation The Pan African-Asian Women’s Organization of the artist Rania Lee Khalil and Aisha Mershani’s Apartheid wall. As we transition from the midlevel gallery to the lower one, the wall in between showcases the photographic works of Yazan Khalili.

In “Landscape of Darkness,” the photographs, while mostly dark, invite parcels of warm light into the background. “As they walked toward the light, the city slowly moved away from them until it vanished into the light. At that instant, darkness declared itself a landscape that united this fragmented land and served as a platform on which exiled space could be reclaimed (Our Land 4).”

In the final gallery on the lower level, we have video installation pieces from Fouad Elkoury in Ruins. As the video clips change every few seconds, we see fixtures, statues and buildings, some of which are whole and some of which are fragmented. “The juxtaposition of the three screens agitates the viewer, posing the questions: “Which ruins are valuable? Which ruins are to be preserved, and which are to be removed?”