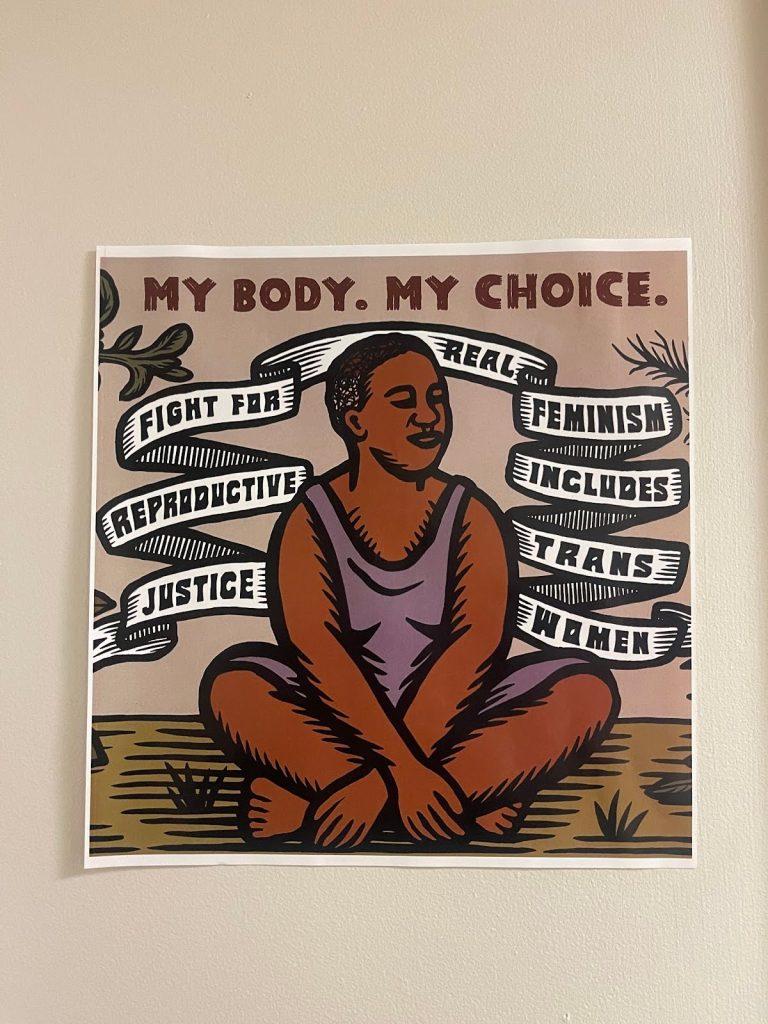

Dr. Shameika Williams, assistant professor of the Public Health Department, moderated a discussion for Black Maternal Health Week (April 11-17) in conjunction with the Social and Environmental Justice Institute at SUNY Old Westbury. The New York State Department of Health recognizes Black Maternal Health Week to raise awareness about health disparities, address medical racism, and advocate for birth justice amongst mothers and birthing people. This year’s theme is “Our Bodies STILL Belong to Us: Reproductive Justice NOW!”

The “Reproductive Justice Now” panel featured four Black women with expertise in healthcare and the intersection of patient rights, policy, and applied practice. The panelists were Dr. Martine Hackett MPH and Associate Professor of Hofstra University; Leticia Rios, RN, MSN, IBCLC, PhD and Nurse Educator at NYU Winthrop Hospital; Amina Woods, LCSW, CD, a Clinical Therapist and Doula of NYC Citywide Doula Initiative; and Medgine Sanon-Ellis, JD, LLC the Chief EEO Officer of NYC Commission on Human Rights.

Dr. Williams opened the discussion with acknowledgements for the enslaved Black women Anarcha, Betsy and Lucy, whose trauma was used to pioneer early gynecology under Dr. J. Marion Sims. Upon their exploitation by Dr. Sims, they each became skilled medical practitioners as they learned to care for one another throughout surgical recovery.

Dr. Williams opened the panel with the question, “Why do we need to bring attention to Black Maternal Health?” Amina Woods, licensed social worker and doula, responded, “We’re in the midst of a crisis… I’ve had enough experience to notice how important the bond, the relationship between a mother and child is. It’s foundational. When we lose a mother to childbirth, it not only affects the children, but it affects the entire family, it affects our community, and essentially it becomes a global issue.”

A lack of maternity care providers, particularly midwives, coupled with inadequate postpartum support systems, contributes to the U.S. having the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world according to the Center for Reproductive Rights. Medgine Sanon-Ellis, who currently holds a Juris Doctor and Master of Law, reflected on her own birthing experiences in a hospital where she felt doctors were overlooking her needs.

“Being in a hospital setting where I was trying to do my best to advocate for myself, I realized the importance of having someone who can do that in a space where I am unable to do that.” She recalls having to seek out advocacy from her employer, after a biased accusation of using drugs while pregnant. This heavily influenced the work she’s done advocating for birth justice, as well as the rights of disabled incarcerated individuals.

Dr. Williams shared a report from the CDC that stated, “50,000 women in the United States suffer from pregnancy complications annually. Black women are at least three times more likely to die from a pregnancy related cause than compared to white women. Higher exposure to structural racism is consistently associated with adverse perinatal and birth outcomes.”

Dr. Hackett reflected on the statistical data behind the maternal mortality rate. During her time with the New York City Health Department, she conducted reviews investigating the leading causes of fatalities in hospitals, which mostly happened from hemorrhaging and pulmonary embolisms. She noted that at least 60 percent of these investigated cases were preventable, claiming that it’s imperative to note the pre-existing conditions of a patient in order to make a thorough assessment.

“What were the living conditions?,” she began, “What were the conditions of the stressors around that person before, and during, and after their birth?”

As a doula, Amina Woods’ perspective of hospitals differed significantly from the other panelists. She believes that the hospital system takes away the autonomy of birthing people and “developed a reputation for being the expert,” leading to choices being made on behalf of the mother and child. Neonatal nurse Leticia Rios, who currently works in the NICU, addressed the importance of broader competent care in a medical setting. “We don’t have enough diversity within the field to really open, or increase awareness of these different lived experiences.”

Dr. Williams reminded listeners that these birthing outcomes are not only limited to poor minority women. Women of higher socioeconomic status, such as Serena Williams and Beyoncé, both endured pregnancy complications met with scrutiny and distrust. Along with being unheard, Black women are often seen as “hostile” or “combative” when they advocate for themselves in a hospital setting. Williams added, “We need to start naming explicitly, that this is racism.” Dr. Hackett believes that once there is more understanding and connection from being “unwoke to woke,” that there will be more of a cemented call to action.

As we consider cultivating a safe birthing experience for mother and child, the fight for reproductive justice includes the community construction needed to sustain a safe, healthy, and happy environment for child caretaking. “Reproductive Justice Now” was an insightful discussion that is especially relevant, in a time where women’s bodies are so heavily politicized.

By amplifying the voices of Black women, advocating for policy change, and investing in culturally competent care, we can reverse these medical outcomes. It’s more important to note that it isn’t just a public health issue, it’s a human rights issue that affects both our present, and our future.